Re-bidding for business you already have is a challenge of biblical proportions.

There may be millions of dollars of revenue or profit on the line, and hundreds of jobs at stake within your business. And that’s not even taking into account the fallout should a major customer defect – very publicly – to a competitor.

Yet many incumbent suppliers vastly underestimate this challenge, and exactly how huge it is going to be.

Described in the Bible in the Book of Revelation, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse represent the evils to come at the end of the world. The first horseman represents Conquest; the second, War; the third, Famine; and the fourth is Death.

In long-term customer relationships, the four horsemen of incumbency are Complacency, Confirmation Bias, Protest, and Shiny Object Syndrome.

Incumbents need to be alert to presence and impact of these four horsemen, or they will trample all over your efforts to win again.

The first horseman: Complacency

Have you heard the term ‘incumbency disease’? Complacency is an obvious symptom.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, complacency means self-satisfaction, especially when ‘accompanied by unawareness of actual dangers or deficiencies’.

Complacency can creep into any long-term relationship. If you’ve been with your partner for a while, you can probably remember when date nights and the ‘dress to impress’ phase gave way to takeout and tracksuits on the couch.

If you think that complacency couldn’t possibly be an issue with your major customers – not when they have you so comprehensively loaded up with KPIs and contractual requirements – think again.

Delivering against customer expectations is not a selling point, no matter how challenging it may be. In deciding to hire you, the customer killed off other options. If you want to win again, they expect more than simply what they are paying you to do.

As an incumbent supplier, complacency is a problem if:

Your team is so bogged down delivering against expectations that they are unable or unwilling to try anything new

Meetings are frequently cancelled, by you or by the customer

You stopped sending reports a while ago, because the customer stopped reading them

Left unchecked, complacency can lead to communication problems, which can erode the customer relationship you have worked so hard to build.

The second horseman: Confirmation Bias

This one is harder to spot than Complacency, and potentially even more insidious.

Confirmation Bias is our tendency to notice new information only when it confirms what we already believe.

First named by psychologist Peter Wason in the 1960s, confirmation bias shows that human beings aren’t rational in the way we process information - particularly when we are emotionally involved.

I recently asked a group of CEOs whether their people only ever gave them good news about their company’s most important customers. The burst of rueful laughter showed just how common this is.

A study by research firm Kapta found that 38% of CEOs had been blindsided with bad news from their team within the last 90 days. It is highly unwelcome to find out there is a major problem with a customer when there is no time to fix it – like when a tender for an existing contract is just about to drop.

As an incumbent supplier, confirmation bias is a problem if:

All your team feeds back to you is positive news

The prevailing narrative is that you’re already ‘the best’, and that competitors don’t have anything to offer the customer

Any inconvenient information that doesn’t support this narrative is stifled, glossed over or ignored

Left unchecked, confirmation bias can drill a lot of holes through your offer – holes that are obvious to the customer, and to competitors.

The third horseman: Protest

As the incumbent, your work is highly visible, and the customer’s team has seen you warts and all. While some may be fans, others won’t be, and their voices can be loud when agitating for change.

Incumbents are vulnerable to a protest vote in any long-term relationship, whenever individual needs on the other side are not being met.

We see this regularly in politics, where protest votes demonstrate dissatisfaction either with the choice of candidates, or with something that is going on in the political system.

For example, in the recent Wentworth by-election, this Sydney harbourside electorate – held by the conservative Liberal party since Federation, and considered one of the safest seats in Australia – fell to high-profile independent Dr Kerryn Phelps.

Previously the seat of deposed Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, Phelps achieved a swing of 29.19% by attracting protest votes from a large number of previously ‘rusted on’ Liberal supporters. An Australia Institute poll found that Mr Turnbull’s toppling was the biggest influence on ex-Liberal supporters (44%), followed by the government’s perceived inaction on climate change (28%).

As an incumbent supplier, you are vulnerable to a protest vote if:

The customer’s needs have changed, and you are not seen to have quickly or adequately responded to them

Vocal stakeholders aren’t getting what they need from you, even if you believe they are too low in the pecking order to really matter

There has been a change of personnel in the customer’s team, and the newcomers don’t know you, or have a preference for someone else

Left unchecked, protest votes can result in negative noise from detractors and distractors, which can drown out the more positive voices of your customer advocates and supporters.

The fourth horseman: Shiny Object Syndrome

Here is a depressing reality check for incumbents; studies show that people like new things, simply because they are new.

Researchers at the University of York tested this idea by asking study participants to play a popular video survival game called Don’t Starve. In the first round, everyone played the same way. In the second round, half the group was told that their game would feature an “adaptive artificial intelligence” (AI) that would tweak the level based upon a player’s experience – even though this wasn’t true.

The “adaptive AI” group reported being more entertained by the game in the second round. They were more immersed in the game world, and expended more cognitive effort to play. All because they thought they were playing a new and improved version of the game.

There is a biological reason why we crave newness.

The mesolimbic dopamine system is the most important reward pathway in the brain. Sometimes called the ‘molecule of happiness’, scientists once thought that dopamine was related to feelings of pleasure only for things we’ve already done. However, it has recently been discovered that dopamine may be more related to anticipatory pleasure – looking forward to something that hasn’t happened yet.

During pleasurable moments, dopamine is released, causing us to seek out a pleasurable activity over and over again. This may be why it is common for people to book their next holiday not long after they have returned from the last one.

As an incumbent supplier, you are vulnerable to Shiny Object Syndrome if:

You are not constantly coming to the customer with new ideas on how they can compete better and do business better

Competitors are taking on this role, either in person or through broadcast channels such as social media, conferences and industry events

New ideas are being generated and discussed – but not by you

The recency effect tells us that the most recent experiences are best remembered. When your customer has a short memory for the great things you did, combined with a strong motivation for future reward, you had better be doing everything you can to ensure that the source of future reward is you.

Why don’t we see these horsemen coming?

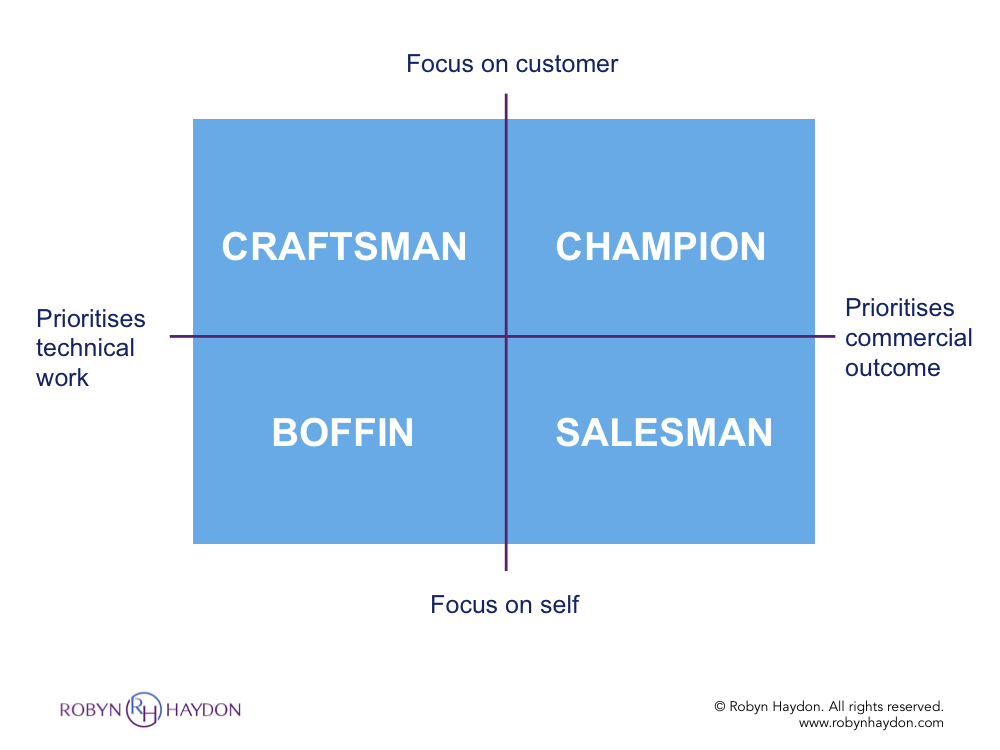

There is a gigantic energy slump that takes place between bidding and re-bidding. Most suppliers spend this phase with an almost entirely internal focus on delivery.

This is where your incumbency advantage – the ability to know more, learn more, and influence more than competitors – can be quickly, and often invisibly, eroded.

Incumbents who face a re-bid without a clear plan or any impartial, third party perspective are at risk of losing from entirely preventable factors.

Getting external support is more vital in the 12 months prior to a re-bid than at any other time – including winning the business in the first place.